Reporting Highlights

- Lost Investments: People who invested with a Dallas HomeVestors franchise, once touted as the largest, accuse the owner of operating a scheme that cost them tens of millions of dollars.

- Red Flags: HomeVestors says its franchises follow best business practices. But investors say lax oversight allowed the “We Buy Ugly Houses” brand to be used to further the scheme.

- Company Responds: HomeVestors has denied responsibility for the franchisee’s actions, saying its franchises are independently operated. It has sued the franchise owner.

These highlights were written by the reporters and editors who worked on this story.

Ronald Carver was skeptical when his investment adviser first tried to sell him on an “ugly houses” investment opportunity eight years ago. But once the Texas retiree heard the details, it seemed like a no-lose situation.

Carver would lend money to Charles Carrier, owner of Dallas-based C&C Residential Properties, a high-producing franchise in the HomeVestors of America house-flipping chain known for its ubiquitous “We Buy Ugly Houses” advertisements. The business would then use the dollars to purchase properties in which Carver would receive an ownership stake securing his investment and an annual return of 9%, paid in monthly installments.

“Worst case, I would end up with a property worth more than what the loan was,” Carver said of the pitch.

Carver started with a $115,000 loan in 2017. And sure enough, the interest payments arrived each month.

He had worked three decades at a nuclear power plant, and retired without a pension and before he could collect Social Security. He and his wife lived off the investment income.

The deal seemed so good, Carver talked his elderly father into investing, starting with $50,000. As the monthly checks arrived as promised, both men increased their investments. By 2024, Carver estimates they had about $700,000 invested with Carrier.

Then, last fall, the checks stopped. The money Carver and his father had invested was gone.

Carrier is accused of orchestrating a yearslong Ponzi scheme, bilking tens of millions of dollars from scores of investors, according to multiple lawsuits and interviews with people who said they lost money. The financial wreckage is strewn across Texas, having swept up both wealthy investors and older people with modest incomes who dug into retirement savings on the advice of the same investment advisor used by Carver.

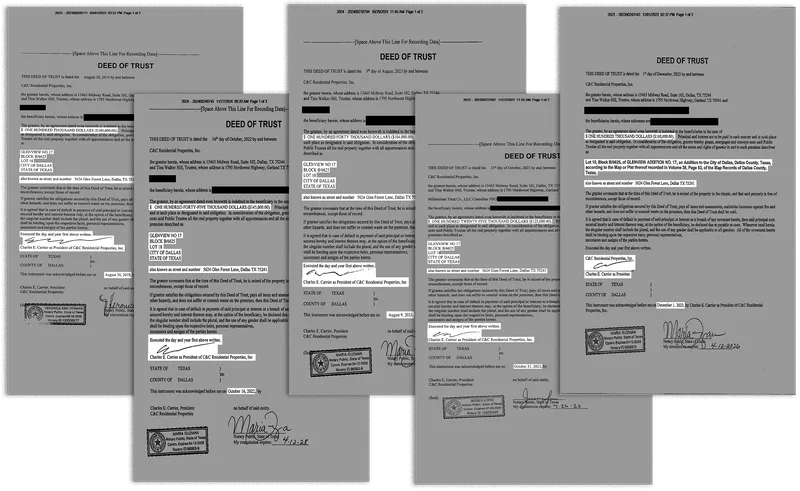

As early as 2020, Carrier had begun taking out multiple loans on individual properties — some of which he never owned. In cases reviewed by ProPublica, as many as five notes were recorded against a single property, far exceeding the property’s value. Carrier also failed to properly record many deeds that were supposed to secure the loans, accumulating more debt than he could ever repay while investors remained unaware they had no collateral for their investments.

“It’s incalculable the amount of damage this guy did,” said one investor who lost about $1 million and asked not to be named to avoid embarrassment and not to interfere with a criminal investigation into Carrier’s scheme. “He’s ruined some lives.”

Carrier, who declined an interview request, said in a brief phone conversation that he’s not trying to avoid responsibility for the harm he caused. “When this thing finally stopped, it was completely driven by me saying ‘enough’ and going to the people and saying, ‘Here’s the mess I’ve created,’” he said. “This is a mess created by me.”

Investors also blame HomeVestors. For nearly two decades, Carrier used the company’s carefully cultivated brand as the “largest homebuyer in the United States” to gain investors’ trust. They accuse HomeVestors of failing to provide oversight that could have prevented the fraud, despite claiming to hold its franchises accountable for best business practices. In its answers to their lawsuits, HomeVestors has denied responsibility for Carrier’s actions, claiming its franchises are independently operated, despite earning hundreds of thousands of dollars from Carrier’s business.

HomeVestors revoked Carrier’s franchise on Oct. 24, about the time interest payments stopped arriving in investors’ accounts. The company said it had received a tip on its ethics hotline — created in 2023, after ProPublica detailed predatory buying practices by multiple franchises. When confronted by HomeVestors, Carrier admitted that “he and his business had entered into debts that they could not pay,” a HomeVestors spokesperson said. The company reported him to the FBI. In May, HomeVestors filed suit against Carrier for trademark infringement and for not indemnifying it against these lawsuits.

“We take all allegations of misconduct incredibly seriously as demonstrated by our decisive action,” the spokesperson said. “It is truly disheartening for us that anyone who lent Mr. Carrier money was misled or harmed by his alleged fraudulent activity.”

Now, Carrier is under investigation by the Department of Justice, according to a recording of an April call between the lead prosecutor and potential victims. (The FBI and DOJ declined to comment.) A judge in one of the many lawsuits against Carrier has deemed allegations of fraudulent loans to be true because Carrier never answered the complaint. And the investors are in a race with one another to recoup even a small amount of what they lost, by either waiting for the DOJ to pay restitution, suing Carrier or trying to foreclose on properties still left in his portfolio.

Just months after learning they had lost all of their investments, and before any restitution could be paid, Carver’s father died.

Credit:

Obtained, collaged and highlighted by ProPublica

A Top-Performing Franchise

In 2005, Carrier opened a HomeVestors franchise in Dallas, where HomeVestors is headquartered. In the early days, records show, he relied on a handful of institutional lenders to finance his house purchases. Soon, the Wharton School of Business MBA who had come to house-flipping following a career at Pepsi and a food service equipment company, started cultivating his wealthy friends for loans.

Carrier didn’t fit any stereotype of a glad-handing huckster with a bad loan to sell. Those who knew him describe him as a serious person, “cordial but very direct.” He always had files in front of him, constantly focusing on his business. It made him seem trustworthy, one investor said.

At HomeVestors, he was held up as a model franchise operator. C&C Residential Properties routinely made the top volume and top closer lists and was even named franchise of the year. Carrier led training sessions at company conferences and described his business as “the largest and most successful HomeVestors franchise in the United States” — a claim that remained on the website for Carrier’s business through early May.

“Chas Carrier, for maybe 15 years, was one of the golden boys at HomeVestors,” said Ben Ahern, who over two decades worked for a HomeVestors franchise and later owned one before leaving the company in 2021. “Internally, it was like, ‘Do whatever Chas Carrier’s doing.’”

It isn’t unusual for HomeVestors franchises to rely on private investors to finance their house-flipping. Banks aren’t typically interested in house-flipping loans, which are often short-term and riskier than a standard mortgage. Because of that risk, investors who lend to house-flippers earn a substantially higher return.

To further minimize their risk and ensure they had a legitimate ownership stake in the house, savvy investors would verify the transaction with an independent title company to research whether there were other liens against the property and then record the deed with the county recorder. But many of Carrier’s investors, after years of consistent payments led them to trust him, let Carrier handle recording the deeds and did not confirm that he’d done so.

As Carrier grew his business, he began relying more on individual investors. ProPublica identified through public records at least 124 people who have lent money to Carrier since 2009. Not all of them have lost money.

Carrier’s search for new investors was aided by Robert Welborn, an investment adviser in Granbury, Texas, southwest of Dallas. Welborn had built a network of clients in Granbury, a city of about 12,000 people on the Brazos River, through church, friendships and referrals. Many of his clients were older and had modest nest eggs, which Welborn said were “well diversified.” He said he built a relationship with Carrier in 2012, after researching his background for about two months. That Carrier was a successful franchisee lent him credibility, Welborn said.

“I never imagined the No. 1 franchisee with a fast-growing franchise company, HomeVestors,” would defraud investors, he said.

At the time, Welborn also solicited new investors with invitations to steak dinners where they would hear his pitch. An investment in Carrier’s business, according to Welborn’s sales material, which also featured the HomeVestors caveman mascot, Ug, was both lucrative and secure. “Your investment is protected,” the sales material assured potential clients.

For loans he sent Carrier’s way, Welborn earned a 2% commission, he said. Welborn had at least two dozen clients who invested with Carrier, most of whom had multiple loans to him, according to a public records search. He would not comment on how many of his clients invested with Carrier.

Many investors were happy for years — in some cases, more than a decade. The interest payments came in like clockwork. A lot of Welborns’ clients relied on the payments for retirement income.

“I was real tickled with it,” said Tom Walls, 85, who said he lost $50,000 of his retirement savings by investing with Carrier.

Some investors noticed small problems — a payment that arrived a few days late or an error on the paperwork to secure the loan. But Carrier always fixed the problems promptly, investors said.

“When you have this 10-year continuous, pleasant and mutually beneficial relationship, you build up a great deal of trust,” said John Moses, who estimates he lost more than $1 million to Carrier.

Looking back, the investors who spoke with ProPublica said they wished they had taken those warning signs more seriously.

Credit:

Max Erwin for ProPublica

“He Just Pencil Whipped Those Deeds”

By fall 2024, Carrier’s payments to his lenders stopped. That’s when the house of cards fell.

Carrier had spent that summer scrambling for money. Not only did Carrier have to make loan payments to scores of investors, but he also needed to keep up with the HomeVestors franchise fees and advertising payments. The company requires its franchises to make regular reports on sales and to open their books for audits, to provide financial statements when requested, and to report all assets and liabilities. Any of those reports could have called into question Carrier’s ability to stay solvent. But, according to former franchise owners and employees, HomeVestors’ audits of its franchises are mostly geared toward ensuring they’re paying all their franchise fees, which are based on sales.

Before Carrier’s tangle of fraudulent loans collapsed and was exposed in court, there were signs of trouble.

In 2016, Carrier was fined by the Texas Real Estate Commission for managing properties without a license. The HomeVestors franchise agreement requires owners to follow all laws and regulations, particularly real estate regulations. In 2020, two title insurance companies issued special alerts on Carrier’s business, advising their title officers not to enter into transactions with him without further legal and underwriting review. Carrier hasn’t paid taxes on some of his properties since early 2023, according to court and public records, another violation of his franchise agreement. Despite the apparent violations, HomeVestors didn’t terminate Carrier’s franchise agreement.

“I don’t really think they do have much in place to prevent something like this,” Ahern, the former HomeVestors franchise owner, said of the company. “HomeVestors at the time didn’t seem to have an internal system policing how franchises finance buying properties.”

A HomeVestors spokesperson said the company focuses on its franchise customers’ experiences selling their homes and does not “dictate” how franchises raise capital. “The more than 950 franchises of HomeVestors are independent businesses with a wide variety of finance options available to them,” the spokesperson said.

Last spring, Carrier began borrowing against his future receipts in exchange for cash advances with exorbitant fees and annualized interest rates that he later claimed ranged as high as 600%. Between May and October, he did this at least seven times, racking up more than $1.2 million in debt beyond what he owed his investors, exhibits included with court filings show. By fall, he owed more than $75,000 in payments a week, according to the original terms. Seven companies filed suit over the cash-advance agreements, accusing him of default. Carrier has denied the allegations of default and has countersued four of the companies, claiming he was charged unreasonably high interest rates.

The lending scheme appears to have fallen in a gray area for state and federal securities regulations. It’s unclear whether the promissory notes Carrier issued to investors meet the definition of a security, two experts told ProPublica.

In October, Carrier’s investors began to confront him about the missing payments, including Jeff Daly and Steve Needham, two of Carrier’s largest investors who had been lending him money for years. Carrier came clean to Daly, admitting he had been running a lending scheme for “several” years, according to a lawsuit Daly and Needham filed. He told Needham he had taken out multiple loans on individual properties without disclosing them to the investors, according to the lawsuit. The two men claimed in their lawsuit, which resulted in default judgments against Carrier, that combined they had lost $13.5 million to Carrier.

The investor who spoke to ProPublica and asked not to be named said in an interview that Carrier broke down in tears when confronted about losing more than $1 million of the investor’s money. Carrier admitted the loans paid for his operating expenses, not for buying and refurbishing houses, the investor said.

“He just pencil whipped those deeds at the end,” the investor said, explaining that Carrier drew up documents but didn’t record them. Because the deeds were never recorded, the investor had no lien on the properties and therefore no collateral. Some deeds were for houses that Carrier didn’t own or never bought, the investor said. “It was a complete fabrication.”

Welborn’s clients, who typically invested much smaller amounts with Carrier, also learned of the house-flipper’s collapse in the fall, when their payments stopped. Carver said that Welborn called him a couple of days after the October payment was due and said, “Hey, I’m sorry to tell you this, but Chas has called me and admitted to fraud.”

Carver said he got in the car and drove to Welborn’s office, where he learned the nightmarish truth that all the money Carrier had taken was gone.

“A Life-Changing Hit”

Investors are deploying a variety of strategies to get their money back — some of which pit bigger investors against smaller ones and early investors against more recent ones. Those who acted quickly are recovering some money through foreclosures and lawsuit settlements. Although Carrier is denying allegations in lawsuits brought by the cash-advance companies, he’s not fighting individual investors who are suing him. Three of their lawsuits have resulted in judgments against Carrier, and he has so far not defended himself against the others.

Welborn said he’s doing his best to help his clients recover their money by providing the necessary paperwork, connecting them with buyers for the houses used as collateral and researching lien histories on the homes. When he first learned of the scheme, Welborn tried to convince his clients to sign on with his lawyer to sue Carrier. The lawyer, Anthony Cuesta, hoped a court would seize Carrier’s assets to help recover the investors’ lost funds. But he quickly learned there were too many investors and not enough equity in the properties to fund the litigation. Now, many of Welborn’s clients are waiting for the FBI and DOJ to act, while wealthier investors are foreclosing on properties and making them ineligible to be used for restitution. Welborn said some of his clients have been paid restitution through a DOJ-appointed real estate agent’s sale of Carrier’s properties, but he declined to provide details.

Carver isn’t optimistic: “We are not going to get a dime.”

At least one investor went after Welborn individually. According to a Securities and Exchange Commission disclosure, the claim was settled for $130,000. In his response to the SEC disclosure, Welborn denied breaching fiduciary duty to the client and said he “resolved the claim to avoid controversy.” Welborn told ProPublica that $120,000 of the settlement came from the sale of the house used as collateral for the family’s loan and he paid $10,000 for their attorney fees.

Welborn said he’s “devastated” by the loss of his clients’ money. “But every day I drag myself to work with God’s help and spend most of my day helping lenders with their own personal restitution battles,” he said.

Some investors said they will have to go back to work after having retired or are scrambling to find some way to replace their lost income.

Carver wishes he had paid more attention to red flags, like paperwork errors. But the monthly checks were so reliable, he didn’t listen to his gut. Or his wife.

“Every time I added money, my wife would say, ‘Don’t do it,’” Carver said. “My mother, too. She would push on my dad not to add any more. But he liked getting the monthly check.”

Carver’s dad, Larry, believed it was the best performing investment he had ever made. When the money disappeared, Carver went to work trying to recoup some of it. Maybe he could write it off on his taxes, he thought. He wanted to get at least something back for his dad. But Larry was in ill health, and in February, he died.

“My dad passed thinking he lost all of his money to this guy,” Carver said, adding he hopes Carrier “goes to jail for a very long time.”

The investor who asked not to be named said the loss was “a life-changing hit.” He had retired at 53, after sticking it out in a job he hated until his stock options vested. When he finally quit, he put the money into Carrier’s business and lived off of the monthly payments. He may have to go back to work.

“He was an arrogant son of a bitch,” the investor said. “It was gone before he told anyone there was a problem. That’s the unforgivable piece. He squandered it all away. And he had to get backed into a corner before he admitted it was all gone.”

Byard Duncan contributed reporting.