” frameBorder=”0″ class=”dcr-ivsjvk”>

To help map the layout, former detainees, who were often blindfolded during interrogations, used techniques such as remembering the number of steps taken to go between rooms.

After the “reception”, the violence continued, with regular beatings during the twice-daily cell searches and, most viciously, during interrogations. Two buildings were identified as the main torture sites inside Taganrog. Former inmates recalled hearing the screams coming from these areas.

Serhiy Taranyuk, a former Ukrainian marine detained in Taganrog, said he was often interrogated in a room sparsely furnished with a chair and a table. “You go in, you are immediately thrown on the floor, you start to get beat and cut … Then, when you are ready to tell them something, they tell you to sit down,” he said. Taranyuk said he was forced into making a false confession.

All Ukrainian prisoners who passed through Taganrog reported horrifying and sustained torture, including civilians and female prisoners. Shylyk, a former soldier who was a civilian at the time of her detention, was beaten with batons all over her body, subjected to electric shocks, threatened with rape and attacked with dogs. Oleksandr Maksymchuk, a prisoner of war who spent 21 months in Taganrog across two separate stints, wrote in testimony obtained by the Guardian of repeated beatings, electric shocks, suffocation and a technique where guards wrapped prisoners from head to toe in sticky tape and then “used them as human furniture”.

Shylyk mentioned a room containing an electric chair: “I was put in the electric chair twice … with a device that attached clamps between my toes. Then they turned on the current.” She described overhearing guards complaining about having to keep the electrocution time to under two hours to avoid killing inmates, as deaths meant more paperwork.

Another dedicated torture room was used to hang handcuffed detainees upside down in a foetal position, their knees strapped to a bar, for 10-15 minutes while being severely beaten. In some locations, shocks were administered using a Soviet-era battery-powered field phone called a TA-57. The technique, nicknamed “Putin’s phone” by prisoners, involved attaching wires to earlobes, the nose or genitals.

Labuzov was repeatedly assaulted by guards demanding he confess to mutilating Russian soldiers. “During one of the interrogations, the investigator asked me to state my rank and position. But he didn’t even listen to who I was … I was immediately hit on the head with a wooden hammer.

“This investigator said: ‘Tell me something interesting so we can stop beating you.’” Labuzov said he was then shocked with electrical wires and hit with a baton and a chair leg.

On another occasion, Labuzov recalled, his palms were burned with a lighter. Once, he was taken to the boiler room and pushed waist-deep into a stove used to heat water, then placed on the meat-cutting table in the kitchen, where he was threatened with a knife.

Others recounted psychological pressure that included forced indoctrination, forced reciting of patriotic Russian poems, and repeated physical and sexual threats.

The cells were overcrowded, with eight men squeezed into a space built to house half that number. Labuzov also recalled another presence constantly watching over the prisoners. “In all four cells where I was, there was a portrait of Putin,” he said.

FSB interrogations

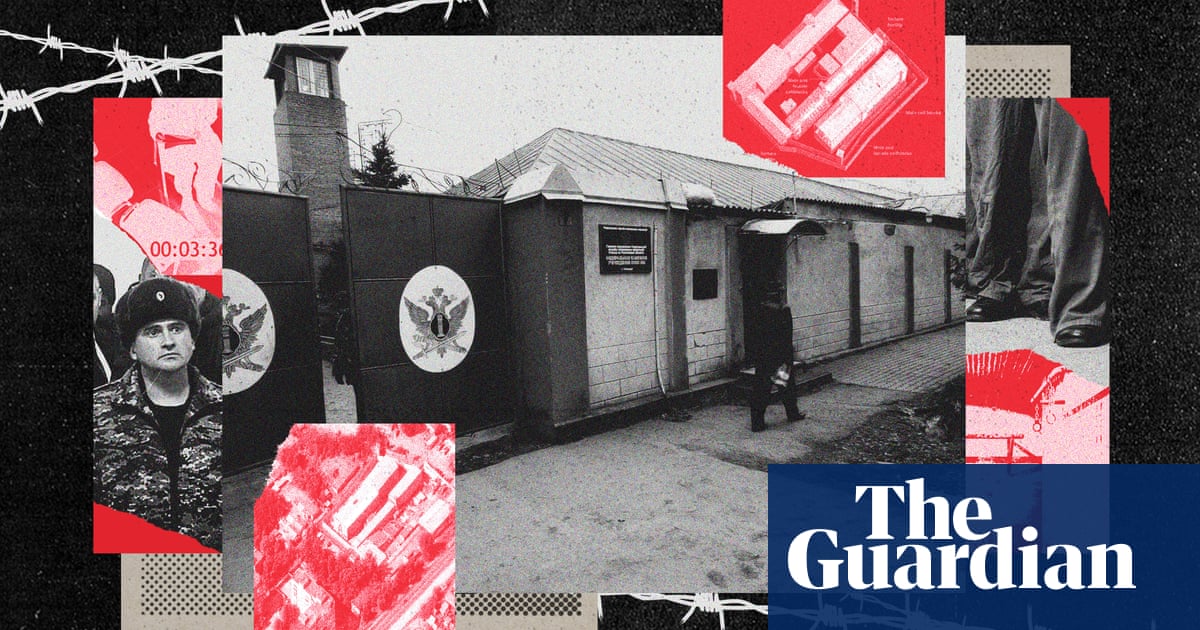

Since November 2022, public information suggests the Taganrog facility has been headed by Aleksandr Shtoda, who took over from the previous head, Gennady Bodnar. Shtoda, the son of two postal workers, was born in a village not far from Taganrog, and before his current role he had held a management position at the prison in 2019 and 2020.

One prisoner recalled Shtoda frequently advising detainees to take Russian citizenship. He was often polite, and even joked with some of the inmates. There is no evidence that he personally oversaw any interrogations or torture. But as head of the facility, he was ultimately responsible for the conditions in which prisoners were held.

Reached by Telegram voice call, Shtoda, 44, hung up. He then read follow-up questions sent by text but did not answer them or a later formal request for comment. The consortium also made efforts to contact Bodnar and a further 35 current and former employees of the Taganrog facility identified through prisoner testimony and open-source research. Most either did not answer calls, immediately hung up or denied working there. Two claimed conditions at the jail were “excellent” while one denied Ukrainians were held there at all.

While prison staff oversee the day-to-day running of the facility, officers from Russia’s FSB security service are in charge of the torture system and conduct the most important interrogations. They control the cases of known dissidents and push for confessions. To back up the FSB, Russia has deployed special units of the FSIN prison service to work on Ukrainians, and they reportedly carry out much of the actual violence.

Testimony obtained from three sources formerly inside the system, shared exclusively by the human rights group Gulagu.net, all pointed to a decision taken in the early weeks of the war to encourage physical violence.

One former senior FSIN official recalled meetings in the spring of 2022 in which the head of the St Petersburg FSIN branch, Igor Potapenko, appears to have told commanders they would in effect have carte blanche to use violence. It seems unlikely Potapenko was acting on his own initiative, and international observers believe ultimate responsibility for these policies, which were applied across the prison service, lies with the Kremlin.

“It wasn’t phrased explicitly as ‘go beat them’ but it was understood. It was communicated down the chain, from the general and his deputy to the commander of the special forces unit and then to the soldiers, that we were to ‘work hard, do everything possible’. That was the euphemism. But everyone understood what it meant. The message was: ‘Do what you want,’” claimed the source.

In contrast to previous assignments inside Russian prisons, when officers wore body cameras to provide a semblance of accountability, now there would be none. “There would be no video recording of any violent actions. That was stated clearly. No documentation, no oversight,” the source recalled.

FSIN and Potapenko, who was recently appointed deputy governor of St Petersburg, did not respond to requests for comment. The Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov also declined to comment.

By analysing reports from the UN and Ukrainian intelligence, the collaboration located 29 Russian-run detention centres where torture had been reported. The facilities can hold an estimated 18,000 people in total, according to public directories. A total of 695 separate forms of torture were recorded. The information suggests Ukrainian detainees have been scattered across Russia, held as far as 600 miles from the border with Ukraine.

The sources said FSIN special forces units were sent on month-long rotations around different Russian regions, ensuring they never formed a connection with prisoners.

Valeriia Subotina, a press officer for the Azov brigade who spent months in Taganrog, confirmed that the guards would rotate roughly every month. According to a Ukrainian intelligence source, FSIN special forces units from Chechnya, Dagestan, North Ossetia and Rostov, with the group names Grozny, Orel, Bulat and Rosna, were deployed at various times to Taganrog.

The guards took care to give little away about their identities. Blindfolds were frequently used for prisoners, and detainees were forbidden to look out of windows. Guards addressed each other using call signs instead of names. One called himself “wolf”, another “shaman”, a third used the codename “death”. All wore balaclavas or other face coverings, suggesting a systemic concealment of identities in order to avoid future accountability.

One former senior FSIN official claimed the original rationale for using torture was to extract information that might be useful to Russia’s military forces or civil administrations in occupied areas. “Information about targets, training sites, preparations, the names of commanders, people who might have had useful connections, even civilians who could be of interest.”

Reports suggest the abuse was also used as a tool for humiliating Ukrainians, often with a marked ethnic element of denigration. Oleg Orlov, the Nobel peace prize-winning Russian rights activist, said the basic system of kidnapping and disappearance of “disloyal” civilians was familiar from Russia’s Chechen wars. “But there is also something new. This continuous, regular cruelty and torture over months and years, this long-term torture for whole groups, I never heard of this in the Russian prison system before,” he claimed.

Subotina said a few of the guards she encountered appeared torn: “They said quietly that they have no choice … that they had no options but to follow orders.” Most, however, seem to have carried out their work with enthusiasm.

‘Outside the legal field’

The majority of civilians are held, for months or years, without any charge. Families may eventually receive a terse confirmation that their relatives are being detained “for opposing the special military operation”, using the Kremlin’s term for the war. These prisoners are known as “incommunicado”. They do not have the right to send letters or receive parcels and Russia often will not even confirm at which prison they are being held.

Often, the first that relatives will hear about where their loved ones are is when those released in an exchange give testimony about the people they shared a cell with.

Legal experts say the framework by which Russia is holding the civilians it seized on occupied territories is unclear and not based in law. “There is no official crime in the Russian legal code of ‘opposing the special military operation’. All of this exists outside the legal field. It’s an absurd situation; even in Stalin’s time there were always charges,” said Vladimir Zhbankov, of Poshuk.Polon, an NGO that helps people look for their loved ones.

One Russian lawyer who works on Ukrainian cases said: “There are people who have been imprisoned for years and we don’t even know where they are. There is no access to them. We periodically send requests to ask where they could be. But in response … they say according to their data there has never been such a person, never detained.”

Access to prisoners in Taganrog is said to be even harder than in most facilities. “It’s impossible for a lawyer to get into Taganrog. I show up and they give me a written refusal: ‘I am declining the services of a lawyer.’ It doesn’t name any lawyer, just says ‘lawyer’ in general, and is signed and dated,” said one lawyer who tried to take on a case of someone held at Taganrog.

The few who still do this work have to carry a huge burden. “Lawyers have to be social workers and psychologists too. It’s very high-risk, it’s emotionally extraordinarily difficult. We are the only people who have access,” said one legal source.

“A lawyer I know saw their client who had been in Taganrog, and the prisoner was in such a bad condition that the lawyer cried for three days,” the source added.

Enduring threat

According to a Ukrainian intelligence source, as of autumn 2024 there had been at least 15 cases of Ukrainians dying at Taganrog, based on witness statements from detainees who returned in prisoner exchanges. One died from torture during interrogation, four collapsed and died during the violent “reception” upon arrival, and in a further 10 cases specific data was not available.

“There was never a doctor in the colony, only a paramedic,” Labuzov said. “When prisoners were unwell, she would come and just ask what was wrong. And she didn’t even give them pills.” If the condition was serious, an ambulance was called from the local hospital, but it often came late, sometimes not until the next day. “I know for sure that one man died like that,” Labuzov said.

In recent months there have been reports of improved conditions in Taganrog, and there are suggestions it has been returned to its prewar purpose. While the torture rooms may have fallen silent, they can still be used to instil fear.

“Taganrog works as a threat now,” said the Russian legal source. “If they say ‘we’re going to send you to Taganrog’, many people will sign whatever you tell them to.”