Have you ever wondered what goes on inside the minds of criminals? What makes someone break the law despite knowing the consequences? It turns out, many offenders have their own ways of justifying their actions—rationalizations that help them make sense of what they’ve done or even convince themselves it was somehow acceptable. In this curious exploration, we’ll dive into the psychology behind these justifications, uncover why they matter, and what they reveal about human behavior. So, why do criminals justify their actions? Let’s take a closer look.

Table of Contents

- Understanding the Psychology Behind Criminal Justifications

- Exploring Common Rationalizations and Their Social Roots

- The Role of Environment and Upbringing in Shaping Criminal Mindsets

- Strategies for Challenging Justifications and Promoting Accountability

- Future Outlook

Understanding the Psychology Behind Criminal Justifications

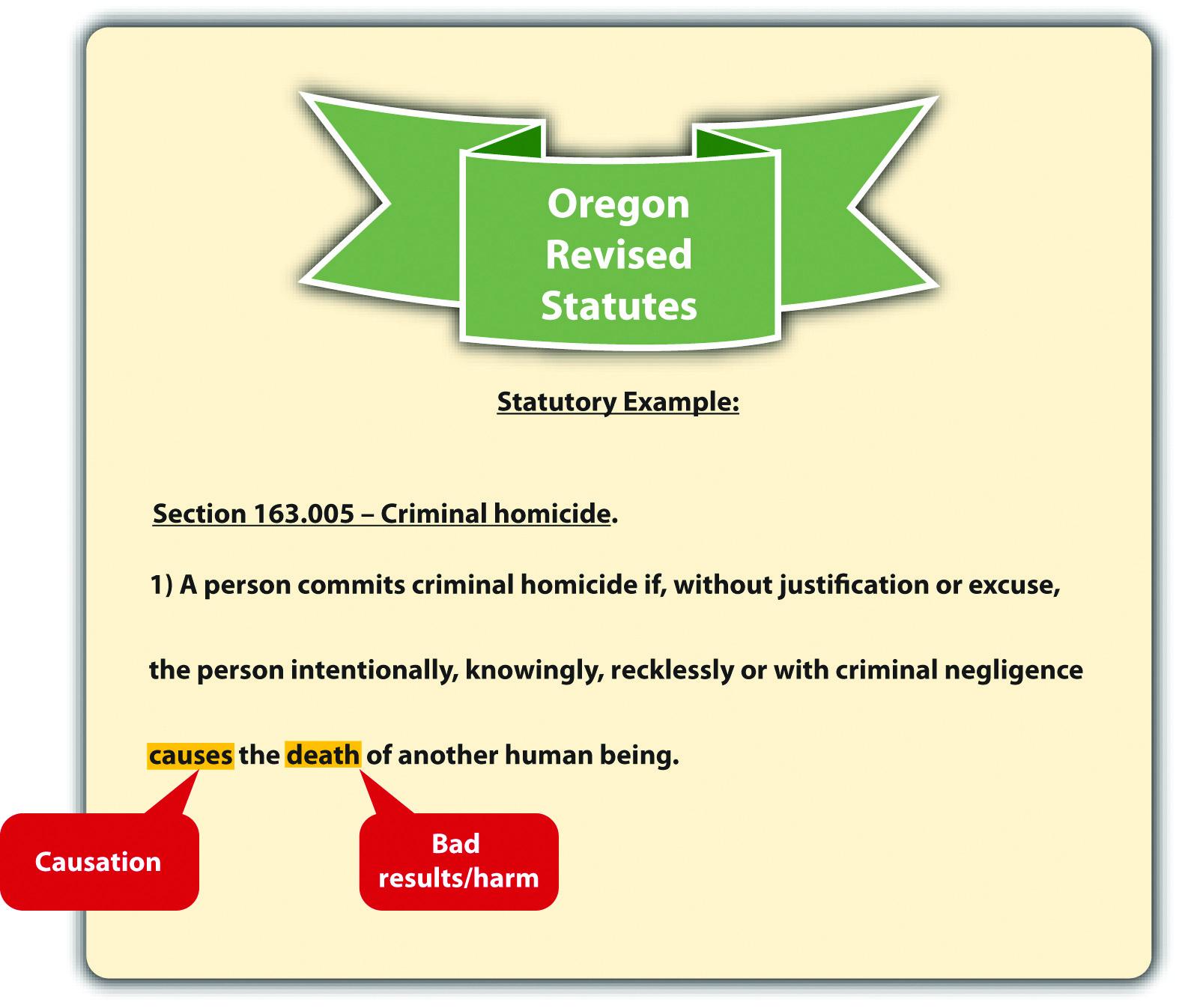

Criminals often engage in a psychological balancing act, where their need to protect their self-image clashes with the reality of their actions. This tug-of-war triggers a series of justifications that help them reconcile their behavior with their internal moral compass. In many cases, these individuals employ cognitive distortions—mental shortcuts that reshape their perception of wrongdoing into something more acceptable or even necessary. For example, they might convince themselves that circumstances forced their hand or that their actions were a form of retaliation against a perceived injustice.

Underlying these justifications is often a deep-rooted desire to evade guilt and maintain social identity. Common strategies include:

- Denial of responsibility: Claiming the act was out of their control.

- Minimizing harm: Downplaying the damage caused to others.

- Victim blaming: Shifting fault onto those affected.

- Appealing to higher loyalties: Putting group loyalty above societal laws.

By weaving these narratives, offenders create personalized frameworks that make their actions not just rational— but sometimes even justified—in their own minds. Understanding this psychological gymnastics illuminates the blurred lines between morality, survival instincts, and social conformity within the complex world of criminal behavior.

Exploring Common Rationalizations and Their Social Roots

When criminals attempt to justify their actions, they often lean on a set of well-worn rationalizations deeply rooted in their social environments. These justifications serve as psychological shields, allowing offenders to maintain a sense of moral order even while breaking laws. Among the most prevalent are the notions of victim blaming, where the target is portrayed as deserving abuse or harm, and the belief that their circumstances left them with no other choice. Such defenses are rarely formed in isolation; they echo the stories, struggles, and societal pressures experienced daily in neighborhoods marked by inequality, neglect, or marginalization.

Social roots also reveal a fascinating interplay between community narratives and individual behavior. For instance, in some communities, criminal acts are framed as necessary survival strategies, a mindset passed down through generations or reinforced by peers. This creates a reinforcing loop where illegal acts are seen less as moral failings and more as rational responses to systemic failures. Common themes include:

- Economic desperation: Poverty pushing individuals toward crime as a means to sustain themselves or their families.

- Distrust in authority: Experiences of biased or brutal law enforcement leading to a disregard for legal boundaries.

- Peer influence: Social pressure to conform to group norms, even if illegal or unethical.

- Normalization of violence: Exposure to aggressive environments where conflict is resolved through force.

Understanding these social dimensions not only unpacks the rationale behind criminal justifications but also highlights potential avenues for intervention and empathy.

The Role of Environment and Upbringing in Shaping Criminal Mindsets

When diving into the roots of a criminal mindset, it’s impossible to overlook the profound impact that one’s surroundings and early experiences wield. From neighborhoods riddled with poverty and limited opportunities to families marked by neglect or abuse, the seeds of justification often sprout in these harsh soils. Individuals raised amidst chaos or instability might develop skewed perceptions of right and wrong, convincing themselves that bending—or breaking—rules is a necessary survival tactic rather than a moral failing. This internal narrative transforms actions that society deems criminal into responses shaped by environment, perpetuating a cycle where circumstances forge the rationale behind illicit behaviors.

Moreover, the community’s role extends beyond mere backdrop; it often becomes an active participant in shaping beliefs. Consider the subtle yet powerful influences that reinforce justification:

- Peer validation: When close social circles normalize or even celebrate criminal acts, individuals gain a psychological shield against guilt.

- Lack of role models: Without positive guidance, distorted value systems can flourish unchecked.

- Systemic failures: Repeated encounters with injustice or discrimination can feed resentment, encouraging rationale rooted in defiance rather than remorse.

In essence, what might seem like pure malintent is often a complex tapestry woven from environmental threads and nurtured beliefs, illustrating just how intertwined upbringing and surroundings are with the mindset that justifies crime.

Strategies for Challenging Justifications and Promoting Accountability

When faced with self-serving narratives, it’s essential to approach the conversation with a blend of empathy and critical inquiry. Challenging these justifications shouldn’t be confrontational but rather focused on unveiling the underlying truths. One effective technique is asking open-ended questions that cause individuals to reflect on the consequences of their actions beyond personal gains. For example, questions like “How do you think your choices impact the community around you?” or “Can you imagine how you would feel if someone did this to you?” can gently nudge offenders to reconsider their perspective. Additionally, highlighting the discrepancies in their logic by pointing out contradictions can subtly expose attempts at deflecting responsibility.

- Encourage self-awareness: Promote honest self-examination through guided conversations.

- Use restorative language: Replace blame with language focused on growth and change.

- Leverage accountability partners: Involve trusted individuals who can reinforce positive behavioral changes.

- Promote consequence transparency: Clearly map out the real-world outcomes of justifications and actions.

Holding individuals accountable requires creating environments where they feel safe enough to own their mistakes rather than fearing judgment. This involves building trust and consistently emphasizing that taking responsibility is a form of strength, not weakness. When accountability is framed as a step toward personal empowerment rather than punishment, people are more willing to engage in meaningful change. Furthermore, integrating community support systems and structured feedback loops ensures that accountability is maintained in a compassionate yet firm manner. In essence, the art of challenging rationalizations lies not in proving someone wrong—but in inspiring them to truly understand and rectify their behaviors.

Future Outlook

As we’ve explored, the ways criminals justify their actions open a fascinating window into the complexities of human behavior and morality. Whether it’s a bid to preserve self-esteem, shift blame, or grapple with societal pressures, these justifications reveal just how intricate the dance between right and wrong can be. Understanding these perspectives doesn’t excuse the behavior—but it does challenge us to think deeper about accountability, rehabilitation, and the stories we tell ourselves. So next time you wonder why someone crosses the line, remember: behind every justification lies a curious mind trying to make sense of choices in a complicated world.